What is the Relative Age Effect?

The relative age effect (RAE) is an effect observed in different environments and relates to the propensity of people born earlier in their year of birth to perform at a higher level than those born later in the year. In 2018, a study by researchers at Nord University in Norway showed that RAE was prevalent in the Norwegian numeracy test in 5th, 8th, and 9th graders.1 This effect has also been shown to be present in athletes in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA, United States), especially in sports such as baseball, softball, men’s tennis, and ice hockey.2 Researchers at Cambridge University have also shed light on the existence of this effect in the UK, particularly in school performance, and have advocated for urgent measures to reduce its significance.3

Is RAE such a major issue?

Unfortunately, the answer is yes. Suppose your 12-year old has signed up to play football, and the age cutoff for his U-13 age group is January 1st 2022. He is born on December 15, so he fits within this cutoff. The problem is that someone born in January of the same year also fits in this category. However, they have had almost one year more of training, development, and mentorship. Coaches also tend to wrongly view this maturity as skill, and as such the children born earlier in the year will benefit from more chances to improve and continue practicing the sport, while children born later in the year have a higher chance of dropping out.

Is RAE present in the Premier League?

The Premier League is an incredibly diverse and exciting league. It is also home to some of the best football players in the world, who have put in thousands of hours of work in physical, tactical, and technical training. However, have these players had an advantage when it comes to the RAE? To understand whether this effect is present in the Premier League, I collected and annotated data for all Premier League teams (2021-2022 season).

My source for this data was the WorldFootball website (https://www.worldfootball.net/). After removing the players without birthdays, I obtained a set of 642 unique players (including youth players that are training/part of the first team), with nationalities and birthdays attached. Only one nationality is considered for each player.

These players comes from 65 unique countries, of which England is the most represented (41.7%), followed by France (5.6%), Spain (4.8%), Scotland (4.0%), Portugal/Brazil (each with 3.3%). Interestingly, there are 12 countries that have more than 10 players, and together they make up for 76.6% of the total number of players in the Premier League. You can see the entire distribution in the figure below.

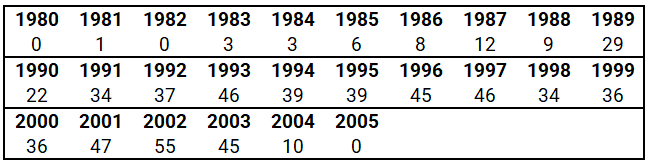

After getting this breakdown, I categorized the players based on the year they were born in.

The majority of the players (378) were born in the 1990 decade, followed by the 2000 (193) and 1980 (71) decades. It would be interesting now to break the analysis down to countries, as different countries have different age cutoffs for youth football. We will first focus on England, as players from this country represent almost 42% of the entire Premier League.

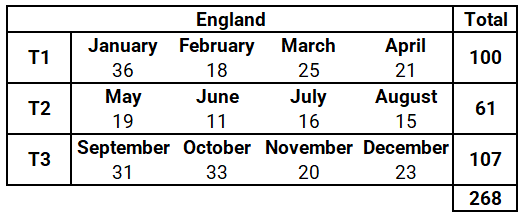

In England, the football group age cutoff is September 1st (the beginning of the school year), and as such players born in June, July, August should be the most disadvantaged, whereas players born in September, October, and November should be the most represented. Let us thus have a look at the year and month of birth of the players born in England.

Interestingly, almost 40% of the English players currently in the Premier League have been born in the last trimester (T3), while 37.3% have been born in the first trimester (T1). The most represented months are January (36 players), October (33), and September (31). At the opposite pole we have June (11), August (15), and July (16). I’ve categorized this in a column chart for easier viewing.

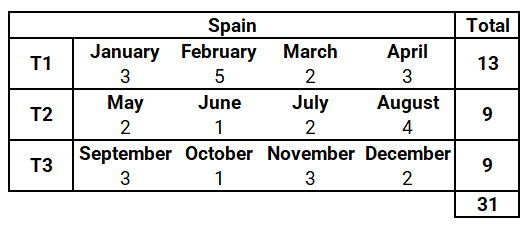

It is quite clear from this graph that players born in June are almost 3x fewer than those born in October, September, or January. To see if this effect is observed in other countries, I’ve chosen Spain as my secondary point of analysis, since I know that the age cutoff is January 1. Thus, the representation should be higher in earlier months (trimester 1), and lower in the third trimester. Let’s see if the results agree with our thought process.

Indeed, the total number of players born in the first trimester surpasses that of the other two, while the most players have been born in February.

Update – December 17, 2021

It occurred to me that I should look at the distribution of birth trimesters across every PL team and see which teams employ the most players in each trimester. Aston Villa have the most English players in their team (19), while at the bottom of the table sit Wolves, with only 5 English players.

Analyzing the data shows us that Arsenal have the highest percentage of English players born in T2 (50%), followed by Brentford (45.5%). On the other hand, the lowest percentages for players born in T2 are seen for Norwich (0.0%), Manchester United (7.1%), and Newcastle (7.7%). Leicester has the highest % of their players born in T3 (61.5%), followed by Leeds (53.8%), West Ham (50%), Newcastle (46.2%), and Chelsea (45.5%). In terms of T1 players, Wolves, Manchester United, Tottenham, and Southampton top the charts, with more than 50% each.

What is even more interesting in this context is that Brentford has the lowest % of English players born in T3 out of all the Premier League teams (18.2%). Of course, the sample size is only 11 players, but the percentages seem to be in line with Brentford’s analytics-based approach to building a team. In 2016, Brentford closed down their academy, created a B team that would play friendlies throughout the year, and focused on finding value where others did not bother looking (i.e., in players born in the second trimester).

The approach of looking for “diamonds in the rough” has worked very well for Brentford so far, as they profited from the discovery and sale of players such as Neal Maupay (bought for a reported fee of £1.6mil from Saint-Etienne, sold for ~£20mil to Brighton), Said Benrahma (bought for a reported fee of £2.7mil from Nice, sold for ~£30mil to West Ham United), and Ollie Watkins (bought for a reported fee of £1.8mil from Exeter City, sold for ~£28mil to Aston Villa). Other good (and relatively unknown) players in their pipeline are Mbeumo, Toney, Norgaard, or Rico Henry, which will likely command high transfer fees once they are eventually sold.

Brentford focusing on players born in the second trimester is thus unsurprising. Their entire transfer model is built on finding value where others are not looking, and this is especially true for young, relatively unknown players, who might have had numerous setbacks in their journey to become professional players.

Concluding Thoughts

This article is not meant to be a rigorous statistical analysis or an exhaustive analysis of RAE. The sample sizes in the Premier League are far too small, the data might not be reliable as it was collected from a website, as well as several aspects have not been corrected for (dual citizenship, where the players have started grassroots football etc). For a rigorous study, the data must be obtained from the FA, anonymized across age groups and corrected for different factors.

What this article is meant to do is raise awareness that RAE might play a role in who gets to play Premier League football. There are far better and more exhaustive studies out there, of which I reference 5, 6, 7, and 8. I also invite readers to read Malcolm Gladwell’s book “The Outliers”, which discusses RAE to some extent and its prevalence in Canadian ice hockey.

The last thing I want to note is that some children who have fallen victim to the RAE could have become excellent footballers. Some, despite the setback of RAE, have made it through the system and are now professional football players. Consider for example Harry Kane (born July 28), and the article published by Matthew Syed in The Times with respect to his rejection from Tottenham, Arsenal, and Watford early-on in his career:

What is going on? The explanation is both simple and revelatory: younger, smaller, less physically mature youngsters are forced to focus their training on skill, guile, craft and technique in order to get through. The obstacles put in their way by unenlightened coaches force them to develop the very skills that will prove a huge blessing once they pass through adolescence and reach physical maturity. As Williams puts it: “While being born later in the year has been viewed as a disadvantage, the paradox is that those who preserve and stay in the game may be blessed with advantages later on that may allow them to profit from a more difficult start.”

Matthew Syed – Why Harry Kane was so nearly lost in game’s age-gap

What the quote tells us is that adversity both builds and reveals character, and those who “make it” despite being born in this trimester are likely to become decent players. Harry Kane was one of the lucky few that made it. It could have been easy for him to give up given the number of times he was rejected, and this would have robbed England of their captain. However, for every success story there are hundreds more that we will never know about, of children who have fallen out of the footballing system simply because their were born at the wrong time.

One must not discount the advantages brought on by being born in the “right” month, and ways must be devised to minimize RAE. Most important, it should be prioritized that children falling out of the footballing system are properly taken care of and helped on other pathways leading to both personal and professional development.

References

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01091/full

- https://usatodayhss.com/2017/relative-age-effect-is-when-you-are-born-more-important-than-how-good-you-will-be

- https://www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/images/109784-birthdate-effects-a-review-of-the-literature-from-1990-on.pdf

- https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/edb044ae-f963-11e7-9a34-94e1b34681c3?shareToken=d2b5e5b7ab6b375eefeb1b652a3903a3

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3761747/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspor.2020.591072/full

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02640411003663276

- https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-40559-001

Last Updated

[ratemypost]

[ratemypost-result]